The Feast of Sukkos was everyone’s favorite holiday in Lipnik. The Rabbi explained it as a celebration of the liberation from Egypt, and the wandering in the desert. A time, he lamented, when “the Jews were more religious than they are these days.” The Talmud commanded that once a year, at the end of the Holy Days, Jews should be build a temporary booth, a sukke, in their yard and live in it for a week. Well, strictly speaking only the men were obligated. But the rest of the family “dropped in” often, and all meals were shared there.

“The sukke reminds us that the Holy One, may His Name be blessed, brought us out from slavery in Egypt,” the Rabbi said each year, “and taught us for forty years in the wilderness before giving us the Promised Land.”

But every holiday had its worldly roots as well, and it was those roots that people who were not Rabbis were most likely to celebrate. Originally the Feast of Booths was a harvest festival, when villagers would live in temporary shelters out in the field, bringing in the harvest, and celebrating their bounty.

“Which is why our sukke today,” Levi whispered, eyes darting about for the Rabbi, “is decorated with gourds and vegetables, and wheat, which no Jew ever found in the middle of a desert!”

By the time they had finished hanging decorations, and putting up a table and benches, it was nearly dark. Miryam and Beylke, along with, the daughters in law, began carrying platters and baskets of food from the house. Levi busied himself with a final inspection of the sukke, the Papa’s duty.

It could be of any size a family needed, as long as it had at least three walls, which could be of any material. The roof had to be natural, however, usually cut branches. The Mishna said so. It had to be solid enough to give shade, but open enough so you could see the stars through it at night. In nice weather it was nice. If it rained, it rained. And when the sun went down on the first day of the feast, the celebration would begin. In the gathering dark, Miryam lit the two candles, saying,

“Blessed are you Adonai Eloheinu, who has commanded us to light the candles of Sukkos.” Levi waved a sheaf of grain and a basket of fruit before them.

“Blessed are you,” he said, “Who gives us the fruit of the earth.”

“Can we eat now?” Anshel begged, from behind his mother, and they all laughed.

“I think we have a wise grandson,” Levi said. “Let’s eat!”

~

After the feast, with stars shining through the roof branches and fresh candles lighted, everyone helped to clear away the dishes. Brandy was brought out for the adults, cider for the children, and the eldest daughter, Mryam’s only daughter, Beylke, began the evening’s festivities with the family’s traditional request,

“Tattenyu!” she called out to her father, “Tell us the story of the Little Sukke!”

“Well, children, gather ‘round,” he said with a grin. This was always the signal for everyone to “gather ‘round,” no matter what age, on benches or on the ground, to listen to Reb Levi’ song.

“You know,” he said, surveying his many children and grandchildren, “Our sukke is not so little.” He gestured with a wide sweep of his arm. “But that is because our family is not so little!” Everyone laughed. Those same words were spoken every year. “And this story, about a sukke a kleyne, is not so much about a little sukke, but about a beloved sukke.” He paused and smiled at them all. “A beloved sukke for a beloved family.

“Of course I cannot tell the story without my fiddle!” he announced. The children all clapped with delight, the adults following their lead. Levi reached into a corner behind the table and brought out his old violin, the one he had used for this moment every year since the children could remember.

He made a great show of tuning the strings, taking far more time than was actually needed. This too was part of the family tradition. The young ones jostled and squirmed with anticipation, inching ever closer to their grandfather. The adults remembered days gone by, when they had done the same thing, in the same sukke. Levi continued to tune his strings, with mock seriousness, until he was interrupted by a young voice in the middle of the crowd,

“Grandpa! The story!” and, remembering his place, “Please!” Levi looked up, in pretended surprise.

“What? Oh. Oh yes, the story!” He drew his bow across the strings, testing his tuning.

“This song is an old, old story about our people. It was first told many years ago, when we escaped from Egypt and wandered in the wilderness on our way to the Promised Land.” Eidel, Beylke’s daughter, raised her hand.

“Were you there, Grandpa?” she asked. Levi pulled on his beard.

“You think because of this beard I’m as old as Methuselah?” he laughed. “No, Eidele, it was too long ago, even for me. But if you are a Jew, it is always just as if you had escaped from Egypt yourself. One day,” he turned serious for a moment, “you will understand.” He looked all around before going on.

“Tonight, everyone, I have two surprises!” again the children clapped gleefully. “Beylke, my Daughter, come sit with me.” Beylke smiled. She knew what was coming. She went quickly to her father, and sat next to him on his bench.

“Here is the first surprise,” said Levi, his eyes twinkling. “Beylke has been taking lessons from me on the fiddle.” Everyone laughed. That was no surprise. They had all heard the sounds of those lessons for months, beginning with scratches and squeals, slowly becoming softer and sweeter.

“She has been taking lessons,” Levi said, “and now she is ready.” He handed the fiddle to her, “and tonight she will play for the sukkaleh tale!” More joyful clapping, and a cheer from Motke, her husband. Beylke blushed, and raised the instrument into position.

“This is an old, old tale,” Levi began, “and it has been told many times, in many lands, in the many languages our people have known. Many of the words have changed many times, and doubtless will continue to do so in the many years ahead.

“This is really a song about two sukkes,” he held up his fingers. “A little one, and a big one. We are sitting in the little one.” Everyone laughed. “Well, I know it looks big, but, believe me it is little compared to the other.

“The big sukke is our people, the Jews. It is so big that millions of us from all over the world fit into it!” A gasp arose among the children.

“But even if our little sukke looks weak, like a little storm could knock it over,” He paused and looked at one of his grandchildren. “Motel,” he asked, “has our sukke ever fallen down?”

“No, Grandpa, never!”

“Aha!” said Levi. “Never! And the big sukke is just like that. Only much bigger. For thousands of years we Jews have faced many trials and dangers. We have faced many storms, and sometimes we were afraid our story might be all over, and that our big sukke would come crashing down. One time it was the Egyptians in the Torah. Last summer it was the Prussians right here in Olomouc! The big sukke has been shaken by so many storms, but has it ever fallen down, Motel.”

“No!” Motel shouted. ”Never!”

“And so, no matter what fears come upon us,” Levi concluded, “we Jews may be shaken, but we will always stand.”

He nodded to Beylke, who began the sweet, plaintive tune, her slender fingers light upon the strings, playing, not with a learned technique, but with an inborn gift. Levi began the to sing.

A sikele a kleyne,

mit breytelekh gemeyne . . .

There was no sound, except for the father’s voice, and the daughter’s violin.

My Sukkahleh is small, not fancy at all

but is especially dear to me.

Thatch I put on a bit, hoping to cover it,

there sitting and thinking I’d be.

The wind was a cold one,

the cracked walls were old ones,

the candles were flickering low.

At times as if dying, but suddenly rising,

as if they did not want to go.

My sweet little daughter

sensing the danger,

got scared and started to cry.

“Father,” she cried,

“Don’t stay there outside

the Sukkah is going to fall!”

Fear not my child, it’s been quite a while

the Sukkahleh still stands strong.

The wind has been worse my dear,

but it’s been several thousand years,

yet the Sukkahleh still stands strong!

Beylke played the last half of a verse as an ending, and lowered the violin. The children looked around, quietly, in awe, at Beylke, at Levi, at the walls of their own sukkaleh that rustled and creaked in the night breezes. Miryam had tears in her eyes; as did all of all the adults.

“Our People haven’t fallen yet,” Levi said, “and we never will.”

Copyright 2017, Walter William Melnyk, All Rights reserved

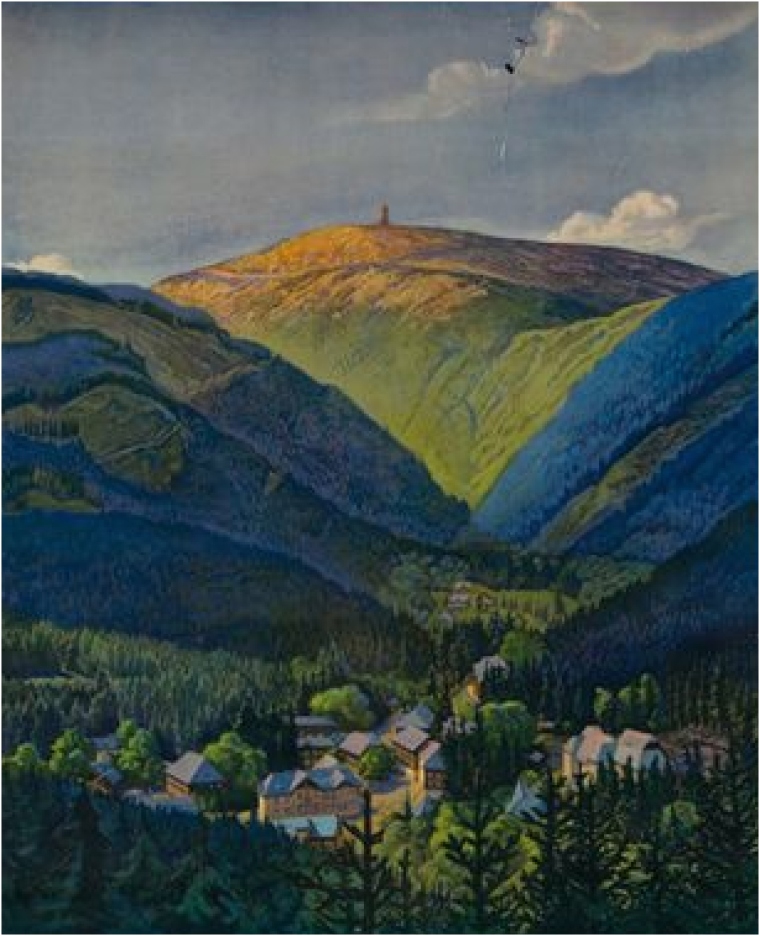

Haunting

Haunting